Military Aircraft Crash Sites

Archaeological guidance on their significance and future management

Military aircraft crash sites are an important part of Britain’s military and aviation heritage. Predominantly dating from WWII, during which there was a massive expansion in air activity over the UK, they comprise the buried, submerged or the surface remains of aircraft, most of which crashed either in combat or training.

Some crash sites are visible, for example as spreads of wreckage within upland environments, or are exposed at low tides. In most cases however, a small scatter of surface debris may mask much larger deposits buried at great depth. The initial impetus for recoveries comes from both eyewitness reports and documentary research. Systematic walking across ploughed fields or a magnetometer are used to identify surface concentrations of wreckage – the debris field – on the basis of which a point or points of impact can be estimated. Given the potential weight of the components and their depth, excavation is often carried out using mechanical excavators. Despite belonging to a period still well within living memory, crash sites have significance for remembrance, commemoration, their cultural value and the information they contain about both the circumstances of the loss and of the aircraft.

It is therefore important that these remains are considered a material matter where they are affected by development proposals and local authority development plan policies. Where crash sites are thought to be particularly valuable, for example where they are spatially well-defined and contain the remains of rare aircraft types, such sites may be considered nationally important and should be treated accordingly in line with relevant Planning Policy Guidance (see under Criteria for Selection, below).

Loss, retrieval and preservation

In the 1960s when memories of World War II were still fresh, aviation enthusiasts began to search for the remains of some of the thousands of aircraft lost over southern England, with a particular emphasis upon those destroyed in the summer of 1940 – the Battle of Britain. Early investigations were often cursory, their primary objective being the recovery of highly prized or sought-after artefacts such as the aircraft’s control column, and it was not at all unusual for sites to be successively excavated and re-excavated by more than one group or individual over several years. As the accessible Battle of Britain period sites were gradually exhausted, efforts focused on those in more difficult locations, until ultimately, attention also turned to crashes from later in WWII.

Documentary sources show us that tens of aircraft were lost on virtually every day of the war. In some cases these may have been due to mechanical failures, in others human error, brought about by fatigue, inexperience or over-confidence. A significant proportion of crashes were the result of damage suffered in combat, whilst the necessity of carrying out flying in adverse weather accounted for many more. In exceptional circumstances a pilot might be able to make a forced-landing, saving both the crew and possibly also the aircraft for future use. Often however, crews were forced to take to their parachutes, leaving their aircraft to crash on its own. More commonly still, one or more crewmembers might be unable to escape, and remained with the aircraft at impact.

Even during the height of conflict, most sites were visited soon after the crash occurred by recovery teams, to remove salvage, human remains, ordnance and in the case of enemy aircraft, to examine the wreckage for intelligence purposes. The size, speed and angle of the aircraft at impact, the surface into which it impacted, and its location all had an effect upon survival, since these were linked to the ability of recovery teams to remove debris. The period of the crash is also important. WWI aircraft were light, relatively flimsy and with airframes of wood and doped fabric, particularly susceptible to fire. Crashed aircraft from this period tended to remain on the surface and were both simple to recover and more vulnerable to subsequent disturbance. Whilst inter-war period aircraft were slightly larger and more robust, they shared more in design and construction with those of WWI than WWII, in addition to which recovery could be conducted more thoroughly in peacetime than under the pressures of war. During WWII aircraft were much larger, more complex and made extensive use of light weight but immensely strong alloys. An aircraft from this period hitting the ground at a steep angle and a considerable speed could bury itself many metres deep, leaving large but fragile components such as the wings on the surface and creating a smoking crater, at the bottom of which might be the engine or engines. Above would be the severely compacted airframe, sometimes containing the crew. Salvage crews could easily remove surface wreckage, and where it was known that crew members were unaccounted for, strenuous efforts were made to recover their remains, a task made no easier by the depth, large quantities of aviation fuel and the ever-present risk of fire. Once the crash site had been cleared and made safe, the crater would be back-filled and the recovery crews moved on to their next task. As a result of contemporary recovery, even where archaeological traces remain, excavation of lowland WWII crash sites may yield on average only approximately 1% (in weight) of the aircraft. In a very few cases up to 10% may survive, but much of this will be severely distorted and difficult to identify. Most WWI and inter-war crash sites will yield even less.

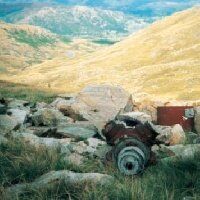

Preservation is generally better for crash sites in the uplands, in the inter-tidal zone, or for those completely submerged, in rivers, lakes or in the sea. As with more conventional archaeological sites, the inaccessibility of upland crash sites has allowed their survival, and although much depleted by souvenir hunting and recovery they represent the only places in England where recognisable or substantial remains still lie intact on the surface. The English Channel and the North Sea also formed the focus for a significant proportion of air activity during the last war, with many hundreds of aircraft being abandoned or crash-landed close to the coastline due to combat damage or technical failures. As examples 234 aircraft of RAF Fighter Command crashed into the sea during the four months of the Battle of Britain, whilst the log for the Skegness lifeboat records that it was called out to aircraft crashes on 61 occasions between 1939-45. Given the relatively low speed of impact in many cases, aircraft which crashed at sea were largely intact at the depositional stage and are more likely to have remained so. The same is true of crash sites situated in the inter-tidal zone. As with other types of archaeological deposits, preservation within these environments has been generally good, despite tide action and exposure to salt water. The majority of the more visible sites have become depleted through souvenir hunting and amateur excavation, but it is likely that other previously unidentified sites remain both intact and in a good state of preservation.

In general terms preservation is often best in waterlogged contexts, where anaerobic conditions slow the oxidisation of metals and allow the survival of organics such as wooden airframe structures, wooden and fabric coverings and parachutes, documents and flying clothing. Heavy clay soils also aid survival by sealing the debris in pockets of oil or aviation fuel, retarding deterioration. Airframes and engines often contain a large amount of aluminium alloy. Although aluminium is in itself relatively resistant to decay, the metal with which it is alloyed has a significant bearing upon its survival.

In many cases investigation may reveal nothing more than small surface scatters of debris. However, in others substantial pieces, including engines, portions of airframes and the equipment and effects of crew members may survive. At a very few sites – chiefly those in inaccessible areas, such as mountains, marshland or inter-tidal zones - large components still lie where they fell.

Why are crash sites important?

Crash sites are a tangible reminder of the extent of air activity over and around the UK during World War II. They offer an important and highly emotive reminder of events which are gradually fading from living memory, and given the losses with which they are often associated, frequently also provide a focus for commemoration. Alongside contemporary documentary records and eye witness accounts, the physical remains also provide a means of reconstructing and in some cases re-assessing our understanding of this aspect of the past.

Crash sites constitute a unique archive of WWII and earlier military aircraft. Many aircraft preserved in museums have either undergone major restoration or are late production models which have been converted to resemble wartime examples. Although the research and skills underlying such restorations are often considerable and serve a valuable purpose in showing what the aircraft may have looked like originally, the remains within crash sites can offer information on manufacturing processes, materials, internal fittings, modifications and even paint finishes which is not available from other sources. Whilst most crash sites' airframes are fragmentary, significant ancillary items such as engines, electrical, radio or navigational equipment and armament often survive. In some cases these may have a rarity value independent of the aircraft in which they were installed.

English Heritage’s Work

Since 1986 English Heritage has been undertaking a national review of England’s archaeological resources with the aim of securing its future management – the Monuments Protection Programme (MPP). As part of the MPP and following on from earlier work on 20th century military remains in England, English Heritage carried out a survey of crash sites in consultation with the Ministry of Defence.

The first stage of this survey was to estimate the total number of crash sites in England. There are no precise figures available for the number of military aircraft lost over Britain, or within its territorial waters during WWI, WWII and the inter-war period. However, whilst records for WWI are particularly fragmentary, those for WWII are better, and allow a general estimate to be made. For example, between 1939 and 1945 RAF Bomber Command lost 1,380 aircraft within the UK whilst either outward or inward bound on operational flights, and along with its Operational Training and Heavy Conversion Units, a further 3,986 aircraft in non-operational accidents. In comparison the Luftwaffe are known to have lost 1,500 aircraft in and around the UK. American losses are harder to establish because contemporary statistics made no distinction between those aircraft lost in combat over continental Europe or those crashing on their return. However, the UK-based VIIIth Army Air Force reported 1,084 aircraft destroyed through non-operational causes. With the addition of losses for RAF Fighter, Coastal, Army Co-operation and Transport Commands, the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm, the Italian Regia Aeronautica, the US IXth Army Air Force, the US Navy and the VIIIth Air Force’s operational losses, the combined total figure for WWII might be expected to be considerably in excess of 10,000 aircraft.

Although records relating to actual crash locations are often imprecise, during WWII a significant number clustered along the southern and eastern margins of England where the majority of air activity took place. As an example, there are estimated to have been around 1,000 wartime crash sites in Suffolk, whilst 500 aircraft are believed to have crashed in Warwickshire.

Research for the MPP survey indicated that crash sites are likely to contain the largest and most intact remains of 22 (24%) of the 90 aircraft types which operated over the UK during WWII, no complete examples of which survive (see Table). Of the British military aircraft used in the UK prior to WWII 67 (62%) of the 93 types are extinct, and crash sites pertaining to any of these aircraft would therefore be particularly valuable. Aircraft in the post-war period have generally been produced in much smaller numbers, and have fared better in terms of preservation with intact examples of all major types surviving. This is due the cost of producing new aircraft, meaning that existing airframes are more likely to be successively upgraded and modified than replaced, with the result that they remain in service far longer than their predecessors. When aircraft go out of service, they tend now to be offered to museums and collectors in comparatively large numbers. Also, from the 1960s onwards, lobbying by the aircraft conservation movement has ensured that the MOD has given greater consideration to preservation when disposing of aircraft. Crash sites from this post-war period are therefore considered to have considerably less archaeological merit.

English Heritage recognises the importance of sites in terms of survival, rarity or historical importance, and would wish to minimise unnecessary disturbance to examples which meet a combination of the following criteria.

1. The crash site includes components of aircraft of which very few or no known complete examples survive. Examples of the commonplace may also be considered of national importance where they survive well and meet one or more of the other criteria.

2. The remains are well preserved, and may include key components such as engines, fuselage sections, main planes, undercarriage units and gun turrets. Those crash sites for which individual airframe identities (serial numbers) have been established will be of particular interest.

3. The aircraft was associated with significant raids, campaigns, or with notable individuals.

4. There is potential for display or interpretation as historic features within the landscape, or for restoration and display as a rare example of its type.

In general terms, sites meeting any three of these criteria are sufficiently rare in England to be considered of national importance.

Management options

All crashed British aircraft in the UK or its coastal waters are deemed Crown property, all Luftwaffe crash sites are considered captured property surrendered to the Crown, and for US aircraft the MOD acts as the representative. Under the 1986 Protection of Military Remains Act (PMRA) anyone wishing to excavate or recover a military aircraft is first required to apply for a licence. Licensing for the PMRA is administered by the Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre (JCCC), a part of the Service Personnel and Veterans Agency. Many crash sites still contain live ordnance and although efforts were made to remove them at the time, a few may also contain the remains of their aircrews. The Ministry of Defence wishes to minimise the potential risks to excavators, whilst at the same time has an obligation to the families of servicemen. Applications for a licence to excavate will therefore be refused where there is a risk that such operations may disturb either ordnance or human remains. A note of guidance, available on application from the JCCC, further explains the procedures and terms for obtaining a licence.

English Heritage fully supports the Ministry of Defence in its aims, but also recognises the historic importance of the remains. To this end English Heritage and Defence Estates/JCCC liaised on the archaeological guidelines included within the cover notes to licenses given under the PMRA. Within this document, paragraphs 9 and 10 relate specifically to the archaeological obligations of recovery groups:

9. The Ministry of Defence licences aviation archaeology under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986. Applicants should be aware that local Councils may have their own requirements in respect of archaeological activity within their area. In particular, Council officials (the Sites and Monuments Records Officers or Historic Environment Records Officer), may ask you to provide them with a project design, or project outline for the work you intend to carry out; depending on the wider historical significance of the location. The Council can also ask you to submit a report to them at the end of the excavation, detailing the results of the dig and the location of any historical artefacts found.

10. On issuing a licence, the MOD will advise if it has been informed of any such requirements and where appropriate will provide a point of contact in the Council. However, it remains incumbent on the applicant/licensee to ensure they check and comply with any relevant Council bylaws and requirements

Close attention should be paid to the excavation methodology adopted. In part this will be determined by the circumstances of the crash and the nature and extent of deposits, but in conjunction with contemporary documentary sources, excavation should aim to recover as much information as possible about the circumstances of the loss. Sampling should take into account the distribution of surface debris in relation to sub-surface remains, together strong indicators of the point or points of impact. As suggested by the PMRA guidance, records of all excavations and field surveying should routinely be made available to the local Sites and Monuments Record/Historic Environment Record, and to the National Monuments Record. The British Aviation Archaeologists' Council’s code of conduct offers additional guidance on methods and techniques, and also provides a useful summary of the information that excavation should be expected to obtain.

Although there is no general database available, advice as to the likelihood of crash sites within a given area can be sought from the British Aviation Archaeologists' Council, whose regional members have specialist local knowledge. Basic data on crashes may also be available in local SMRs. In all cases where the presence of a crash site has been indicated, and it is believed that works may disturb it in any way, a licence must be obtained from the JCCC before work commences.

- In some cases previously unknown remains will be uncovered during development. In such circumstances there is a strong likelihood of the presence of either ordnance or human remains, and the local Police should therefore be informed immediately. If necessary a MOD Explosive Ordnance Disposal Team will be called in to ensure that the site is safe, and until this has been done it is advisable to cease any work in the vicinity.

What's New?

-

The National Heritage List for England is now live on the English Heritage website.

-

Welcome to the HER21 page. This page offers access to the full suite of HER21 project reports.